by Scott Denne, Keith Dawson

Although mobile apps have become an inveterate part of people’s lives, the software used to promote those apps hasn’t found much of a home within customer experience (CX) software stacks. Excepting those few companies whose apps are their business, most customers of large marketing clouds haven’t invested in app marketing. But there are signs that’s changing and with it, a larger universe of buyers could begin hunting for mobile app marketing targets.

Upland Software’s recent acquisition of Localytics marks one of the first instances where a broad CX software vendor has reached for a mobile app marketing provider. Localytics built its business providing app analytics and in-app content personalization, landing customers in traditional industries such as retail, telecom and media. The company generates $20m in revenue and was valued at 3.4x that amount in its sale – above the typical multiple for personalization specialists, a group of sellers that’s had trouble fetching above 3x multiples, as we noted in our recent coverage of Salesforce‘s purchase of Evergage.

Still, it took Localytics about a decade to achieve the size it did, as most businesses in traditional markets have yet to invest heavily in mobile app marketing tools. The idea that all of the CX components (sales tech, martech, servicetech) are being pulled by consumers toward mobility has been conventional wisdom for several years. Companies, though, are just beginning to implement the kinds of planning and technology deployment that will cement mobility at the center of their strategies. The acquisition of Localytics may be a sign that the broader CX vendors view mobility as a potential differentiator and short-term revenue opportunity.

According to 451 Research‘s M&A KnowledgeBase, almost all previous purchases of mobile app marketing firms have been done by buyers from the same category. That’s not to say others haven’t grown a substantial business in app marketing. Companies like Applovin, IronSource and Appsflyer all generate annual net revenue in the nine figures, but have done so with a focus on mobile gaming – a trend we discussed in a recent report.

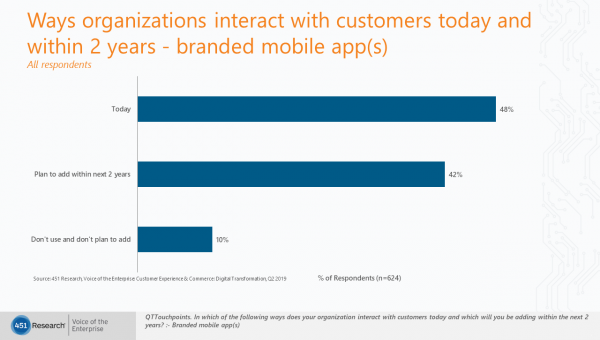

Although industries such as media, retail and telecom haven’t spent heavily on mobile app marketing, our surveys suggest those investments are ramping up. According to 451 Research‘s Voice of the Enterprise: Customer Experience & Commerce, 42% of all businesses plan to interact with customers via a branded app in the next two years (48% say they already do). In that same survey, more than one in three (35%) said mobile marketing software would be among their organization’s highest marketing technology investments in the next 12 months. As customers invest, we anticipate more marketing software vendors to follow Upland in acquiring mobile app marketing capabilities.

BMO Capital Markets advised Localytics on its sale. Cowen & Co. advised the buyer.

Figure 1: