by Brenon Daly

High-water marks only become apparent when the waters recede. As time passes, the pinnacle stands out even more because everything that follows comes at a lower level. We see that in deal flow, too.

Consider the take-private of Ultimate Software, which did indeed prove to be the ‘ultimate’ LBO of 2019. No other deal came close to its size ($11bn) or valuation (11x). On average, the tech companies that got erased off US exchanges after the HR software vendor garnered an average valuation of just a smidge more than 3x trailing sales, according to 451 Research‘s M&A KnowledgeBase.

Now, we have an early entry for the singular private equity (PE) transaction of 2020: Insight Partners’ $5bn recapitalization of Veeam. Both in terms of transaction structure and size, it is an outlier. And it will almost certainly remain that way for the full year, even as PE shops likely put up more than 1,000 prints again in 2020.

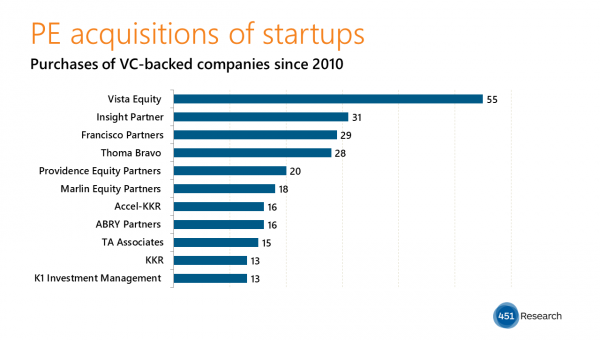

For starters, financial buyers have only just started shopping in venture portfolios, and are significantly underrepresented there. (Our data shows that PE firms over the two previous years have accounted for just 22% of purchases of venture-backed companies, which is fully 10 percentage points lower than the ‘market share’ they hold across all of tech M&A.) Within that, recaps – or a single financial sponsor replacing a syndicate of investors – are only a tiny slice of those deals.

Of course, Insight was already on Veeam’s syndicate, having invested $500m previously. But in most cases, VC-to-PE deals break down due to unbridgeable valuation gaps. (Oversimplified, the discrepancy goes something like this: VCs tend to value startups aspirationally, while PEs tend to value startups realistically.)

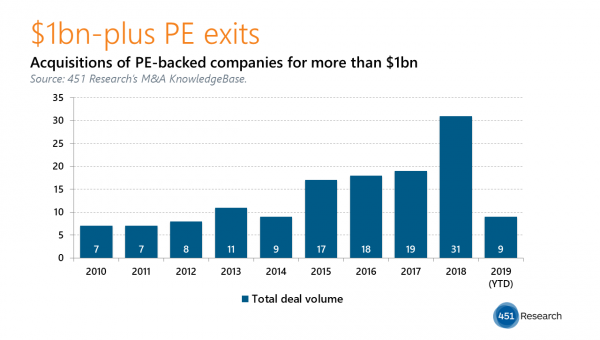

Beyond the unusual transformation of Insight going from minority shareholder to outright owner of Veeam, the transaction is also likely to stand on its own this year because of its size. The M&A KnowledgeBase lists only three tech deals by sponsors over the past year that are larger than the pending recap of the data-protection provider.

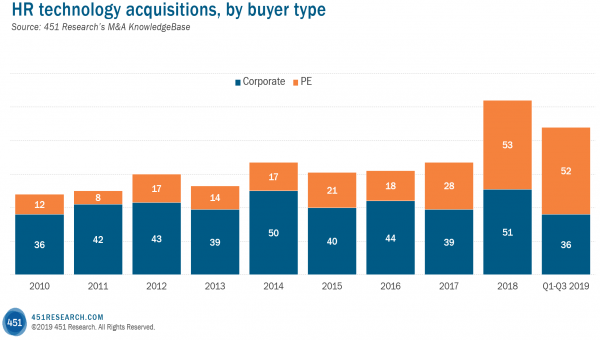

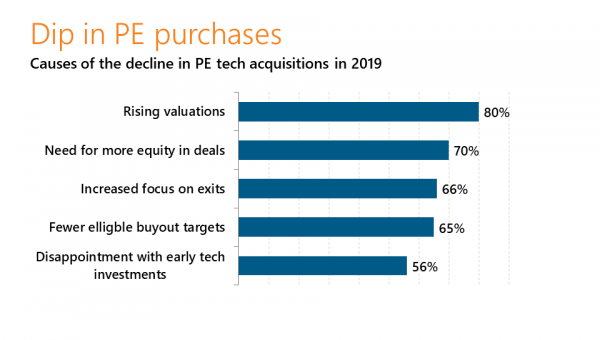

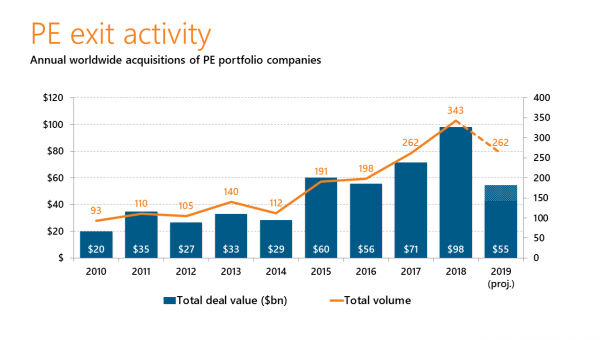

And over the course of the past year, PE business has dried up. Spending on transactions by buyout shops dropped 20% in 2019 compared with 2018, while last year also saw the first decline in the number of PE prints in six years. Further, 2020 may slow even more. In our annual survey of senior tech investment bankers, they told us their pipeline for PE work is not as full as their overall pipeline for the coming year. That’s the first time in three years they haven’t been busier with financial acquirers.