by Brenon Daly

Strategy doesn’t count for much in a shrinking market. Consider all the effort that tech vendors put into profiting from the emergence of the mobile phone, a wonderous device that helped move computing and communications out of the office. Whether through R&D or M&A, companies spent billions of dollars in designing, making and selling the shiny new gadgets that seemingly everyone wanted. And yet, in just over a decade, the trend has largely played out.

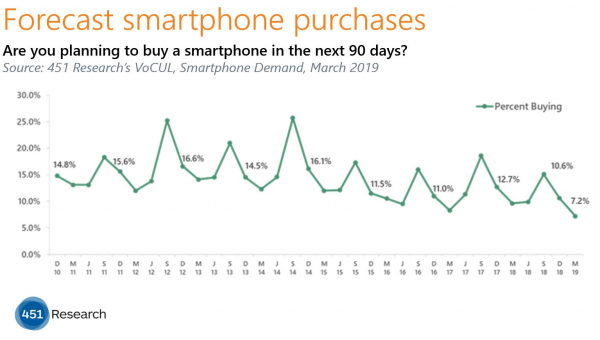

In a recent 451 Research survey, the number of consumers who said they planned to purchase a smartphone in the coming three months slumped to its lowest-ever reading. Just 7% of some 2,800 potential buyers surveyed by 451 Research’s Voice of the Connected User Landscape (VoCUL) indicated that they will be picking up a new device in the next 90 days. That’s about half the level of planned purchases from VoCUL’s springtime surveys at the start of the current decade.

Purchases of smartphones, like most other consumer tech products, tend to be driven by release cycles. New devices mean new buyers. And while that cyclicality still shapes the demand captured in our VoCUL surveys, the overall ranges have come down. Lower highs coupled with lower lows unequivocally point to a market in decline.

Peak to trough, the smartphone market has tumbled from just a few years ago when one in four consumers convinced themselves that they needed to buy a new device to a level now of just one in 14, according to our survey work. As demand for smartphones ebbs to a historic low, the strategies used by various tech firms to supply this once-promising market have been laid bare.

Across the board, companies don’t have a lot to show for their smartphone efforts. (Certainly nowhere near the enduring value created by the emergence of the PC industry in the previous generation.) That’s true whether the company tried to buy or build its way into the handset market. Tech giants that have successfully acquired dominant positions in other emerging tech markets stumbled with smartphones, writing off billions of dollars of their M&A spending (Microsoft) or unwinding deals altogether (Google).

Meanwhile, vendors that stayed in-house and focused on engineering must-have devices undermined their efforts by mistiming or mispricing their phones. (Amazon, the world’s most successful online retailer, couldn’t even really give away its Fire phone.) Even market leaders have resorted to building in gimmicks to spur demand that that blew up in their faces (Samsung’s Galaxy Note 7) or crumbled in their hands (Samsung’s stillborn foldable phone). No matter what they have tried, smartphone makers just haven’t been able to keep buyers coming back for more like they once did.