by Brenon Daly

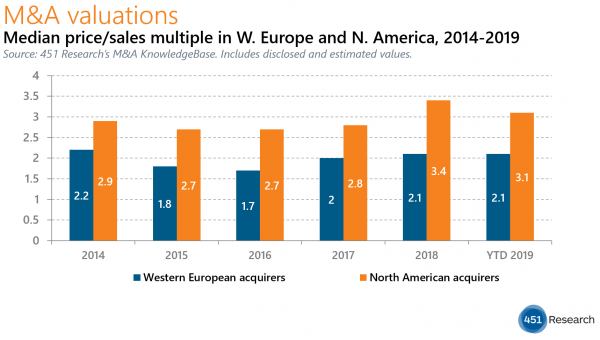

Europe’s underdeveloped venture industry, combined with its slowing economic activity overall, is turning the Continent into a bargain market for tech M&A. Over the past half-decade, Western European acquirers have consistently paid roughly one turn lower than their North American counterparts. The valuation discrepancy on the two sides of the Atlantic is even slightly more pronounced when it comes to VC-backed startups.

According to 451 Research’s M&A KnowledgeBase, Western European buyers have paid a median valuation of 1.9x trailing sales in their tech deals across all sectors since the start of 2014. During that same time, our data shows North American acquirers paid 2.9x trailing sales overall. (To be clear, we are looking at buyers headquartered in the respective regions, regardless of the target’s location. Just to give some sense of scale, over the past half-decade, acquirers in America and Canada have announced nearly three times as many tech transactions as their European cousins.)

In both regions, the broad market multiples have been led higher by the valuations for VC-funded companies. The M&A KnowledgeBase shows European buyers have paid a median of 4x trailing sales for venture-backed startups since 2014, while North American acquirers have been even more generous, paying 5.3x trailing sales.

That’s a fairly substantial premium for any startup, and it’s one that is paid far more often by North American buyers. In fully one of every five tech deals, a North American company picks up a VC-backed startup, which is almost twice the rate of European acquirers. With more plentiful funding, which can fuel faster growth rates, bigger paydays are being found on this side of the Atlantic. When it comes to tech M&A, risk capital can be rewarding.