by Scott Denne, Jessica Montgomery, Michael Nocerino

As the media and telecom giant carves out its position in a transforming television landscape, Comcast acquires XUMO, a streaming video services provider. It’s the latest in a cascade of deals as Comcast and its peers adjust to an ongoing shift in consumer viewing habits. While Netflix, Amazon, Disney and other companies that can throw billions into content creation and distribution have largely locked down the subscription-supported streaming video market, ad-supported video remains up for grabs.

Comcast’s reach for XUMO loosely resembles Viacom’s acquisition of Pluto TV. Both targets provide a streaming video service that hosts multiple video channels, supported by advertising. But where Pluto primarily goes to market via a consumer app, XUMO partners with TV OEMs to preinstall the software into their smart TVs in exchange for a share of the ad revenue generated by the service.

XUMO’s existing relationships with LG and other OEMs give Comcast a valuable distribution channel and, eventually, XUMO’s software could offer a replacement for Flex, the streaming video hardware Comcast hands out to its internet customers. Although terms of the deal weren’t disclosed, those considerations likely lifted XUMO’s valuation ahead of the multiple on Viacom’s year-ago pickup of Pluto (subscribers to 451 Research’s M&A KnowledgeBase can view our estimate of terms of that deal here).

Viacom and Comcast aren’t the only ones inking deals for streaming video content and service providers. Last year saw Altice nab Cheddar in a $200m transaction that followed T-Mobile’s $325m purchase of Layer3 TV and AMC Networks’ acquisition of RLJ Entertainment, a deal that valued the target at $517m, or 5.5x trailing revenue. More acquisitions of ad-supported streaming services could be on the way. 451 Research has confirmed media reports that Fox is considering a purchase of Tubi and Comcast’s NBCUniversal has explored buying Walmart’s Vudu.

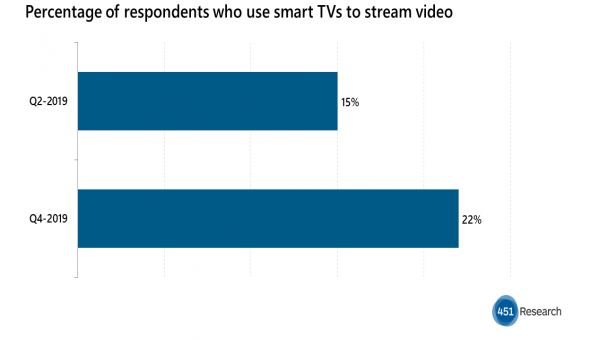

The addressable market for ad-supported services could expand significantly as ownership of smart TVs surges – and our surveys show that to be the case. According to 451 Research’s VoCUL consumer population representative survey, usage of smart TVs to stream video rose by nearly half in the six months between the second and fourth quarters of 2019, with 22% of people saying they use those devices in the most recent survey. (The fourth-quarter data will be published shortly, the second-quarter data can be found here.) A larger market could lead to buyers for additional services, such as Philo, Plex or sports-focused FuboTV.

Telos Advisors advised XUMO on its sale to Comcast.

Figure 1: Changes in video-streaming devices