by Brenon Daly

IBM has wrapped up the single most significant reshaping of its 108-year history. Now comes the hard part.

After more than eight months of review by regulatory officials around the globe, Big Blue officially owns Red Hat. The $33bn deal stands as the largest software acquisition in history – almost twice the size of the second-largest deal in the space, according to 451 Research‘s M&A KnowledgeBase. Corporate deal-makers that we surveyed in December 2018 voted IBM-Red Hat the most significant acquisition of 2018, a year that featured an unprecedented 100-plus tech transactions valued at more than $1bn.

Beyond the sheer scale of the blockbuster deal, the combination promises an outsized impact on IT departments as it pairs IBM’s extensive commercial relationships with many of the largest companies with Red Hat’s close association with many of the most popular technology trends. Most notably, Red Hat – a company that generates some $3bn in sales and is still growing at a solid mid-teens percentage pace – has developed key pieces of open source software for cloud computing (Red Hat Enterprise Linux), OpenStack and containers (OpenShift).

Now that it owns Red Hat, IBM faces a tricky balancing act in getting the hoped-for returns from the massive combination. (Like most large-cap tech acquirers, Big Blue has a decidedly mixed record in M&A. It is in the process of unwinding many of its purchases of business applications, while another relevant acquisition – IBM’s billion-dollar-plus purchase of SoftLayer – has underdelivered.) IBM’s challenges with Red Hat are even sharper than its other acquired proprietary software vendors because Red Hat, an open source software stalwart, had vast technology partnerships, including some with vendors that compete directly with IBM.

Conscious of that, IBM has pledged to preserve Red Hat’s historic neutrality in the cloud wars. (Don’t look for any ‘blue-washing’ of Red Hat now that the deal is closed.) The degree to which IBM follows through on running Red Hat as a stand-alone platform for the increasingly hybrid-cloud world will go a long way toward determining the returns on the deal.

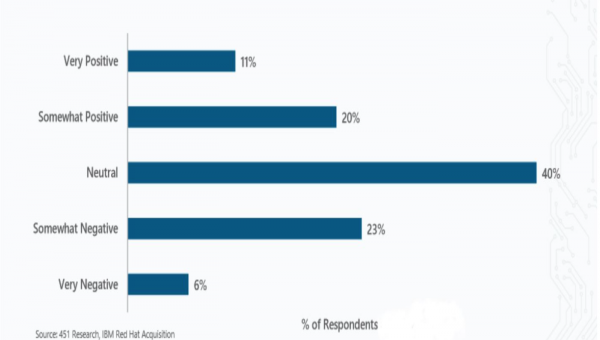

Big Blue should know that the odds are only a slightly in favor of it pulling that off, at least in the view of the one group that matters more than any others: customers. In a novel survey shortly after the deal was announced last fall, 451 Research’s Voice of the Enterprise spoke to several hundred IT executives to get their perspectives on IBM’s plan to purchase Red Hat. The headline finding had a plurality of respondents (40%) indicating they are ‘neutral’ on the deal. Of the remaining portion of IT folks, however, only a handful of respondents said they were more bullish (31%) than bearish (29%) on IBM-Red Hat.