by Michael Hill

Europe is leading the agricultural technology revolution as IoT and other emerging technologies transform large-scale agricultural operations into connected farms. A combination of European farm subsidies and European IoT deployments is boosting acquisitions of European agricultural technology (agtech) companies.

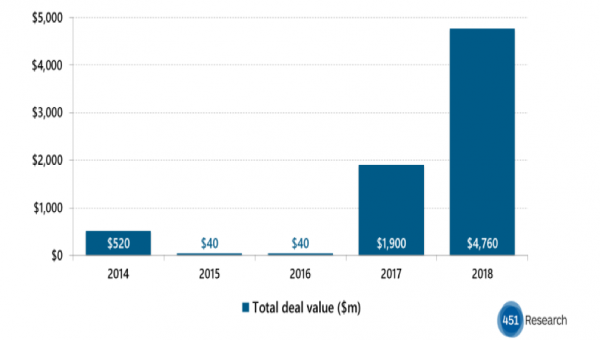

According to 451 Research‘s M&A KnowledgeBase, a record $4.8bn was spent on agricultural technology deals in 2018 – more than the previous five years combined. Of that record spend, $4.6bn went to Europe-based targets, which are currently on pace to exceed 2018 in terms of deal volume.

While a genuine showstopper of an agtech deal has yet to emerge this year, Merck’s $2.4bn reach for Antelliq, a French provider of livestock tracking software, certainly fit that description last year. As in that deal, the emergence of IoT is partly driving the trend (that deal was 2018’s largest acquisition of an IoT company). According to 451 Research‘s Voice of the Enterprise: IoT, businesses are expanding their IoT investments in EMEA. Our recent survey shows 21% of respondents are planning to deploy projects there, up four percentage points from the year before.

Farm subsidies from governments are also bolstering European agriculture, making companies that serve that market more attractive targets. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, since 2014 subsidies for European farmers, such as the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, have grown 8%, while subsidies for US farmers, by comparison, have declined 13%.