by Scott Denne

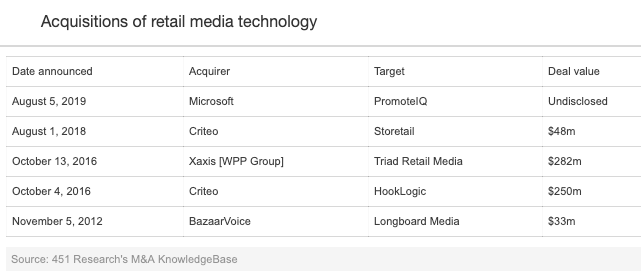

The sudden surge of Amazon’s advertising business has sparked acquisitions of software companies that help retailers become publishers. Microsoft is the latest entrant with the purchase of PromoteIQ, a maker of software that enables retailers to run product ads. As audience monetization becomes a feature of more e-commerce businesses, more deals could come.

For Microsoft, the pickup of PromoteIQ (formerly known as Spotfront) has overlap with its search advertising business. Product ads, often delivered alongside e-commerce search results, are essentially an evolution of paid search advertising. The target’s software provides retailers with workflows and controls to manage their sponsored product listings.

Amazon, more than any other company, has realized the potential for retailers to monetize their apps and websites through sponsored products. As we noted in a recent report, the online retail giant’s advertising business has tripled in less than two years to about $10bn in annual revenue. Despite that growth, the category is nascent enough that there’s not yet a widely accepted name for it. PromoteIQ refers to it as ‘vendor marketing,’ while Criteo and Triad, two of its larger rivals, call it ‘retail media.’

Given the early stages of the market, there are few sizeable players remaining for would-be buyers. Several midsized firms such as Adzerk, Crealytics, Koddi, Playwire and SYNQY offer retail media products. Another vendor, OwnerIQ, enables retailers to monetize purchase intent data gleaned from shoppers on their sites. As Amazon’s advertising revenue continues to balloon, targets in this space could get a look from acquirers in search (Google, Pinterest), e-commerce software (BigCommerce, Shopify) and retail-focused advertising (Quotient, Valassis).