by Scott Denne

Two months into the new year, 2020’s market for venture exits isn’t shaping up to be a continuation of last year’s evenly distributed liquidity. Instead, it’s looking like a repeat of 2018’s blockbuster-but-unbalanced returns. Intuit’s $7.1bn acquisition of Credit Karma marks the latest in an unprecedented pace of mega-deals for VC-backed vendors, at a time when more mundane exits are as hard to come by as ever.

According to 451 Research‘s M&A KnowledgeBase, Intuit’s purchase marks the third time in two months that a VC portfolio company has been bought for $5bn or more. Put another way, one of every three VC-backed tech vendors that have sold for more than $5bn since the dot-com bubble have done so in the current year. Of course, that’s not entirely due to the generosity of buyers – most targets have taken on far more money than their earlier peers to achieve such outcomes. Credit Karma, for its part, raised about $370m (and another $500m secondary investment from Silver Lake). Plaid and Veeam, the two other venture-backed firms with $5bn M&A exits this year, raised similar amounts.

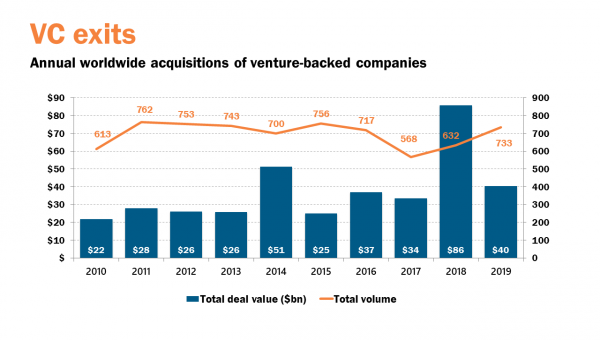

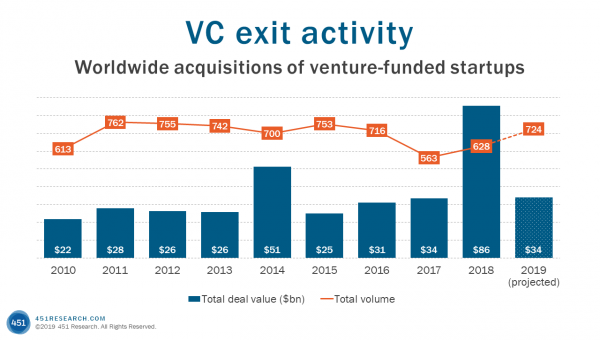

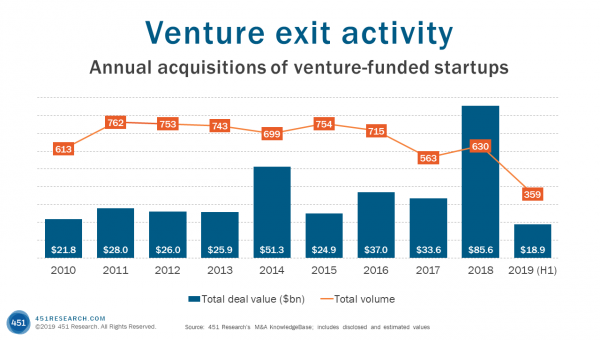

In 2019, VCs divested 739 companies, the first year they’ve crested 700 since 2016, returning to a typical volume of annual exits and no deal values reaching the $5bn mark. Although there are more exceptionally large exits so far this year, they are more exceptional than ever. For most venture-funded startups, buyers are scarce. Our data shows that 94 such vendors have found buyers since the start of the year, compared with 122 during the same period in 2019. That 22% drop comes as the most prolific startup shoppers are curtailing their purchases.

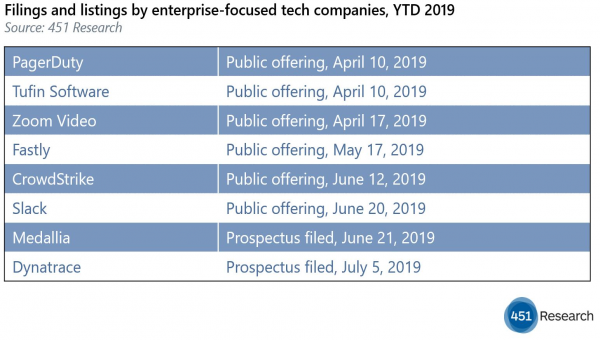

Of the 10 most active startup acquirers since 2010, only four have printed a purchase this year. Microsoft, for example, hasn’t bought a venture-backed company in four months, while Cisco has been on a six-month drought. Oracle also hasn’t printed such an acquisition in the four months since it bought CrowdTwist, a transaction that ended an 11-month streak without a startup purchase. While vendors like Visa (acquirer of Plaid) and Intuit – neither of which had ever previously spent more than $500m on a startup – reach for the occasional rising star, there’s a distinct lack of interest in less-brilliant assets in venture portfolios.

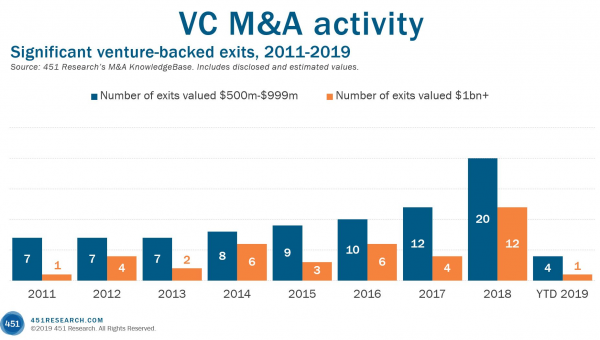

Figure 1: Annual volume of VC exits ($1bn-plus)