The economic protectionism and national isolationism that has brought the world’s two largest economies in conflict has cost both the US and China billions of dollars. Yet the wounds in the ongoing trade war aren’t evenly distributed. So far in the early days of the conflict, China has suffered more damage since it started with more to lose.

That imbalance – and the accompanying vulnerability – shows up in broader macroeconomic implications for the two countries. As my colleague Josh Levine recently noted, China’s exports to the US account for 3.5% of their GDP, while only a scant 0.6% of the US GDP is generated by exports to China.

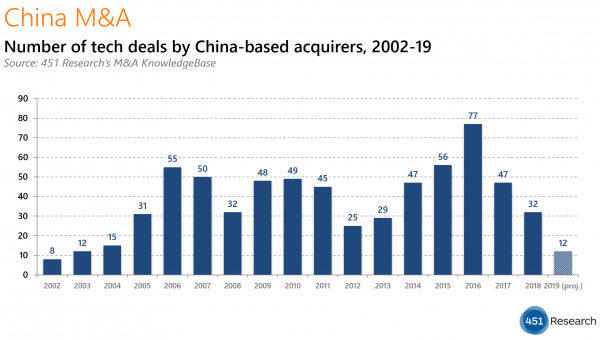

The disparity also plays out in M&A activity, which is also a form of ‘trade,’ after all. As 451 Research’s M&A KnowledgeBase shows, the ledger there is rather imbalanced: Since 2002, China-based acquirers have spent three times more on US tech vendors than the other way around. In that period, China has done more shopping in the US than anywhere else, with American tech firms accounting for one of every six deals announced by a Chinese buyer. (For the record, a majority (60%) of tech transactions by Chinese companies involve a target also based in China.)

More notably, Chinese firms have announced billion-dollar purchases of key tech assets from such prominent US vendors as Uber, IBM and Lexmark. In contrast, there hasn’t been any comparable deal flow in reverse. China’s ‘Great Firewall’ has blocked a lot of business expansion – including acquisitions – by US tech companies in the world’s most-populous country.

The contentious relationship between China and the country that had been its largest supplier of tech targets is just the latest complication in the country’s nascent effort to emerge as an M&A powerhouse. Currency restrictions imposed by Beijing diminished their ability to pay for deals, while the recent domestic economic slowdown has made Chinese companies think twice about taking on any acquisitions. And even if the deals do get done, in the current highly politicized environment, there’s no guarantee now that regulators will sign off on it.

For all those reasons and more, China-based tech vendors have stopped shopping. They are currently averaging just one acquisition a month, according to the M&A KnowledgeBase. That’s just one-quarter the rate at which they were purchasing tech providers in the past half-decade. Assuming that pace holds, our numbers show that Chinese buyers will announce the fewest tech transactions in 2019 since 2003.